I use rsync every day for backing up systems.

While rclone provides some much-needed performance improvements and handling for offsite storage providers, rsync has the advantage of being available virtually everywhere. This includes ancient systems (rsync dates back to 1996), as well as low-spec devices, where it can be difficult to realize advantages from powerful modern tools.

More than just a tool for copying files, rsync is a critical part of many backup routines. It’s that scenario I’m addressing in this blog post: backing up a system’s files to another location.

This is a companion blog post to a video I’m working up, which I’ll link here when finished. 🙂

Installing rsync

You’ll have to install the rsync package on every system that’ll use rsync– both the source and destination systems. It may already be included, rsync is a common enough dependency.

At the terminal, you can check if it’s installed with which rsync. If you get a location back, congratulations! If the prompt returns no output, you’ll have to install the rsync package from your package manager.

The destination (system where you’re sending the files) will require an openSSH server, in order to receive files from the source. If you’re running systemd, you can check for a server with sudo systemctl status sshd. If you aren’t running systemd you probably don’t need a tutorial about rsync. 😛

Installation on various distros

Debian/Ubuntu/Mint/etc

sudo apt update

sudo apt install rsync

sudo apt install openssh-server # for destination systems onlyFedora and derivatives

sudo dnf install rsync

sudo dnf install openssh-server # for destination systems onlyArch and derivatives

sudo pacman -S rsync

sudo pacman -S openssh # for destination systems onlyMaking sure SSH is installed

You almost certainly have SSH installed on your machine. If you manually removed it, you probably aren’t using a tutorial for rsync in the first place.

Modern rsync software uses SSH (Secure Shell) for sending files to a remote system, as well as receiving them. If you aren’t sure, you can check that it’s installed with which ssh.

Using rsync

Using rsync is straightforward:

rsync [flags] [source] [destination]The initial rsync invokes the tool, but let’s go over the other options.

My favorite everyday rsync flags

Dry run

I’m putting this one first because you should get familiar with it: while you’re learning rsync it’s best to do actions as a --dry-run. This will simulate rsync without actually copying (or more importantly, deleting) any data. I’ve been rsync-ing before it was cool and I still --dry-run almost every time I build a new rsync routine. It’s common sense.

Archive

I almost always run rsync with -a for backups: this is the archive flag, and consolidates -rlptgoD into a single flag. This use of rsync will preserve most attributes about your files, will be recursive (copy from subdirectories), and is much easier to remember than most of the other flags. Other than edge cases, it’s what I use every day.

Verbose

I often run rsync in verbose mode (the -v flag). This provides me additional information about what rsync is doing. I don’t always use it, particularly in scripted cases if I’ve built out my own logging and alerting. But even then, sometimes I pipe the results of -v to a text file to make a cheap log of sorts- at least during the testing phases anyway.

Delete

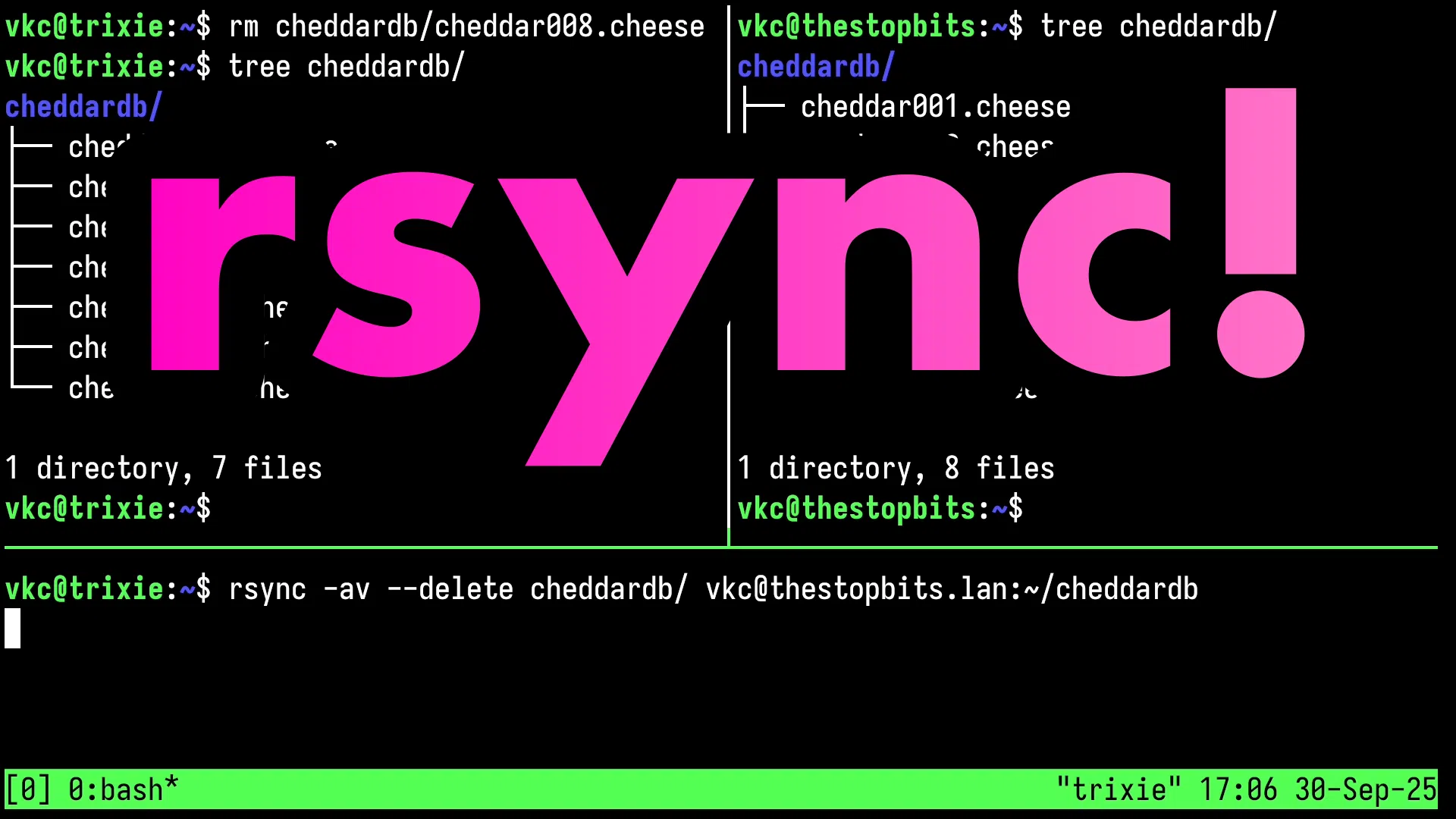

This is scary, but not too scary. The idea is rsync can delete files on the destination that don’t exist on the source with the --delete flag. This keeps two folders in sync and keeps things tidy. I know I dislike going through my backups and finding old duplicates that are wasting space!

The thing about the --delete flag is that it can get you in trouble if you aren’t careful with it. For example, one time I was pulling files (initiating rsync from the backup target instead of my everyday machine), and the remote system couldn’t tell that one of my drives was unmounted. Because I was using --delete, guess what happened to my files on the backup machine?

Because of these sorts of gotchas, we generally recommend that beginners initiate rsync from the source machine and send files to the destination, what we call a push of files. It’s a bit easier conceptually and I will say generally, it works just fine for me. There are edge cases where this is reversed, but by-and-large I prefer pushing when using the --delete flag.

Setting an rsync source and destination

The source and destination format is pretty straightforward: give rsync a path.

For a source example, let’s say I have files in a “cheese” subdirectory inside my home folder. My source might say ~/cheese. That will create a cheese subdirectory inside the destination. If you don’t want this subdirectory to be created (maybe it already exists), you’d put a trailing slash on the end of it: ~/cheese/ instead of ~/cheese.

For a destination, you can specify a local path, but this is probably an inefficient use of rsync: most of the time you’ll be using a remote path over ssh: user@server, followed by a colon, then the path on the destination which will receive the files. And as mentioned above, you can invert this (using a remote path as the source), but generally (particularly for beginners) I do not recommend doing this, particularly not with the --delete flag. If you get things wrong you could delete your system.

So finally an example

OK, with all that out of the way, here’s what an everyday rsync would look like for me:

First, testing it with --dry-run:

rsync --dry-run -av --delete ~/cheese vkc@backup.lan:~/backups/This looks good, the output shows me that it created every file inside my cheese subdirectory over on the backup server.

It put them all in a new cheese subdirectory as well- that may or may not be what you want. Maybe you have other backups in this folder and don’t want to be deleting unintended files? That’s why we dry-run!

So, a modification on this that protects other files in the backups subdirectory would have me placing a slash after cheese, and then manually specifying a cheese subdirectory in the destination, like this:

rsync --dry-run -av --delete ~/cheese/ vkc@backup.lan:~/backups/cheese/Now the cheese stands alone- I’m only moving the files inside the cheese folder, not the folder itself. And I’m specifying a dedicated location for the files to end up: the cheese subdirectory inside the backups directory on my server. Beautiful.

That’s the awesome thing about the --dry-run flag: it gives you the chance to see this stuff before you accidentally delete all of your backups. 🙂

I can see it’s not deleting files I don’t intend, so I’m comfortable giving it a try. Simply remove the --dry-run flag and run it!

rsync -av --delete ~/cheese/ vkc@backup.lan:~/backups/cheese/An untested backup is just wishful thinking, so a quick SSH over to the server is in order to confirm that the files are there, and that everything is as I’m expecting it.

Pro tip: use tmux for lengthy rsync jobs

I know most folks think of tmux as a terminal tiling tool, and yeah, that’s how I often use it. But tmux has a neat trick: you can detach from it, close the window, and go do something else.

Here’s the scenario: I’m SSH’d into a server and preparing to run a lengthy rsync job (or rclone or any other lengthy file transfer really). But I really want to go home for the day and want to shut off my computer.

This is where tmux is a viking. You might need to install the package for your system, but you can run tmux, and then start your long rsync run there. Then detach from tmux with <ctrl-b> followed by the d key.

Now, as long as the computer is running (in this scenario, a server running an rsync task), I can disconnect from the server, and go live my life while the long process runs. I can check on it again by SSH-ing into the server and then run tmux a to re-attach to the session.

But Veronica… rsync is slow

Yup. It is. It’s a very old-school way to do this. But I’m going to argue that’s a good thing in a lot of cases.

If I’m running a virtual server and only have two cores available to the VM, rsync doesn’t have a significant performance difference from rclone, but it is immediately recognizable by other admins. I cannot stress for you how important familiarity and ubiquity are in a professional setting. I will concede that rclone is gaining popularity and might become an acceptable alternative, but it’s still not as commonplace as rsync in scripts or other utilities.

My day-to-day desktop systems might use other tools for big backups, but everyday scheduled backups, like copying my video drafting directory to my NAS, benefit from rsync and it’s ancient, single-threaded nature: I don’t want to devote significant resources to the backup process while I’m working on editing a video. In this case, slow and non-performant is a feature, not a bug: rsync might take its time but it’s not going to interfere with my work, either. When rclone is running full bore I can feel the computer throttle up- you don’t want that during a recording session.

So there’s nuance. Such is life. Anyone telling you rsync is dead is being dishonest, or naive. Use what works for you!

Thanks for reading!

The written version of Veronica Explains is made possible by my Patrons and Ko-Fi members. This website has no ad revenue, and is powered by everyday readers like you. Sustaining membership starts at USD $2/month, and includes perks like a member-only Matrix/Discord space. Thank you for your support!